FOCUS ON

TXEMA SALVANS

Txema Salvans is one of those photographers you need to know if you’re interested in photography as a language and if you’re looking for a solid discourse built with great dedication, not just pretty pictures.

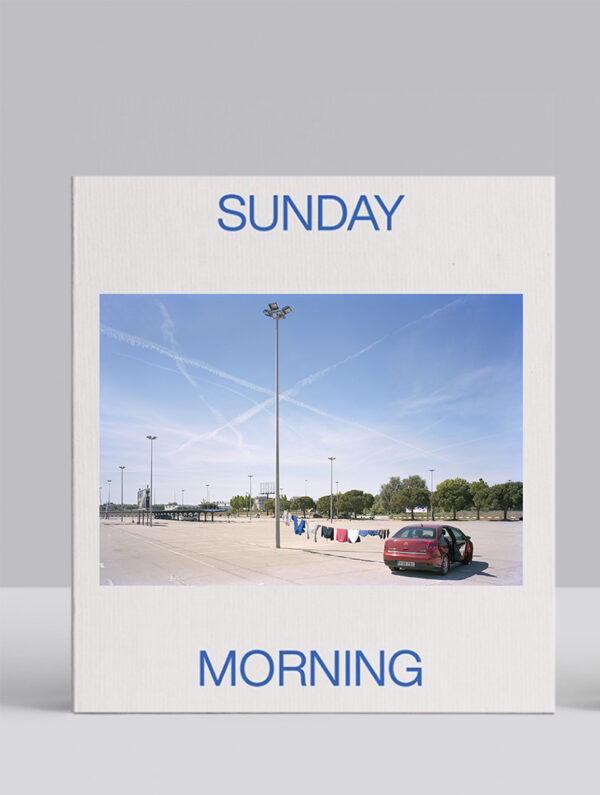

Txema recently published a new book, “Sunday Morning,” which follows in the footsteps of his previous work and which you can buy HERE.

“CARREFOUR, SUNDAY 12 P.M.

For the past ten years, every Sunday at 12 p.m. when the weather is sunny, the photographer, seated on the roof of his van about three and a half metres above the ground, has been welcoming people who come to spend their day off in the Carrefour car park in El Plat del Llobregat, on the outskirts of Barcelona, when the shopping centre is closed.”

Q I’ve been following your work for a while now, and from the beginning, it’s always struck me as something out of the ordinary. In fact, many of your photos have an implicit surrealist feel.

Is that what you’re aiming for, or what you’ve discovered? Or, to put it another way, do you consider yourself more of an auteur photographer or a documentary photographer?

A I don’t think I have to choose between one or the other.

I work from a very literal perspective, very close to reality, but reality, when observed patiently, is already profoundly strange.

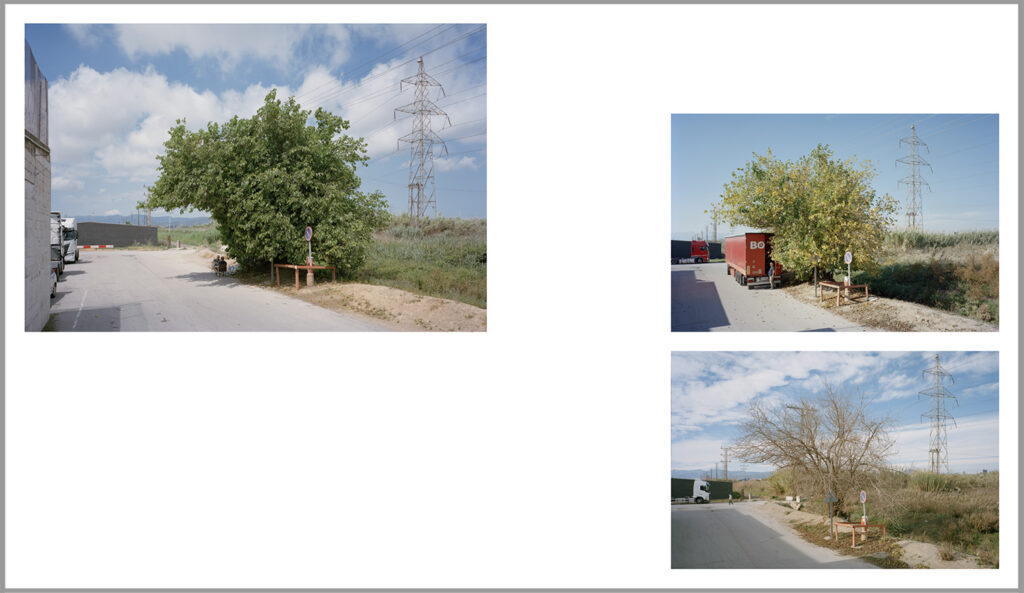

I start with documentary strategies: long-term work, without intervening (beyond the occasional portrait), returning again and again to the same places.

Looking for that empty image, yet one laden with meaning.

I’m not interested in explaining an event or illustrating a specific theme; in editing, I choose photos that challenge the viewer, that are somewhere in between.

In that sense, I do consider myself an auteur photographer. Over the years, a very recognizable style and aesthetic have become established.

To the point that when friends see certain scenes or situations, they immediately describe them as “very ‘Txema Salvans’.”

This recognizability isn’t something I initially sought, but it’s the natural consequence of always working from the same interests, obsessions, and doubts.

Documentary is my method; authorship appears almost as a side effect.

Q Going back to your beginnings, why did you start with photography? And what are you trying to achieve with your work today?

A I studied Biology but abandoned it for photography after winning a scholarship to study at the ICP in New York.

Photography suited my cognitive abilities well; I’m a curious and contemplative person, and photography offers me the possibility of immersing myself in the world from my inner world.

Solitude is also something I’ve grown up with and learned to enjoy, something fundamental for developing my projects, which involve long journeys in my van, sleeping in any corner I can find.

The camera offered me a perfect excuse to be in the world observing without having to justify myself too much. At first, I photographed almost instinctively, without a clear message, but with a very strong attraction to the everyday, to the seemingly banal.

Over time, I came to understand that what truly interested me wasn’t so much the isolated image as the project, the repetition, the passage of time, the accumulation of small variations.

Today, I continue to pursue this: to construct open narratives about how we adapt to the spaces we create, how we inhabit the contemporary landscape, and how, even in highly regulated or artificial contexts, something alive, unpredictable, and human always emerges.

Q Your work is divided into projects. However, there’s a recurring location: the Mediterranean coast. Why is that?

A The Mediterranean coast is a strategic choice, and something biographical. It’s the landscape where I grew up and the one I understand best.

I’m not interested in it as a postcard or an idealized space, but as a territory of friction: tourism, leisure, infrastructure, desire, precariousness, free time, consumption… everything coexists there very visibly.

Furthermore, it’s a profoundly repetitive landscape and, at the same time, full of anomalies. That fits very well with my way of working: always returning to similar scenarios and observing how, within that repetition, unexpected situations arise.

In the end, more than talking about the Mediterranean, I talk about the incredible resilience of our species, which is capable of adapting emotionally and physically to everything. I don’t think there’s a species capable of suffering more than we are.

Q Let’s talk about your latest book, “SUNDAY MORNING.” I’m fascinated by how the parking lot of a closed shopping mall comes to life. Since it’s functional for the mall and closed, it should normally be empty. Are we witnessing a temporary expropriation of this private space, or rather, a momentary appropriation of a disused space?

A The parking lot is a space designed for a single, very specific function: to facilitate consumption. When the shopping mall is closed, that space remains in a kind of limbo, with no apparent use, no real oversight, no narrative.

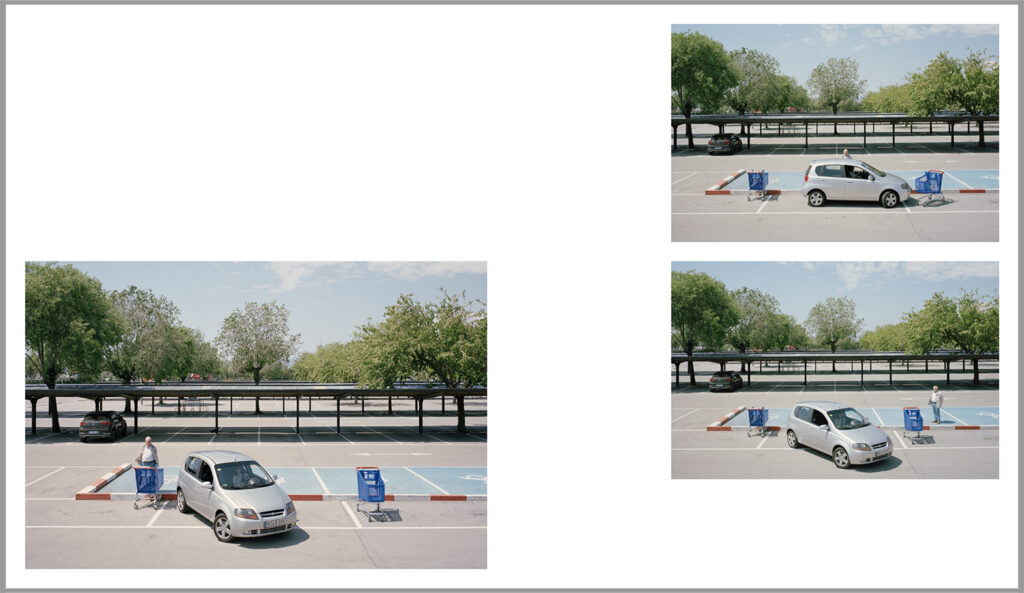

I think the very idea of going to the Carrefour parking lot every Sunday for ten years at the same time, 12 pm, is in itself madness, but I love it nonetheless. It’s like going to mass every Sunday,

or picking up the newspaper every Sunday, or visiting Grandma every Sunday. It’s the everyday, something very human, taken to the extreme. It’s almost the most artistic act, almost above the result. Although I think the result, that is, the book, works very well.

Furthermore, the idea that the entire book unfolds like a single shot, where each photograph is connected to the one that precedes or follows it, gives it a very real, very logical rhythm. It’s as if I were taking the reader by the hand and inviting them to walk around the Carrefour shopping center.

I don’t know if I would call it expropriation, because no one claims that space as their own permanently. It seems more accurate to speak of a momentary, almost unconscious appropriation. People strolling, playing sports, meeting up, celebrating something, or simply passing the time. For a few hours, the place ceases to be a cog in the commercial machine and becomes something else, much more ambiguous and open.

For me, Sunday Morning is precisely about that: about how, even in extremely regulated and designed spaces, life always finds a way to seep in.

Q There are many scenes that are striking in their content, but what surprises me most is your ability to photograph them as if you were seeing something completely ordinary. I think that’s what reinforces that feeling of surreal strangeness.

A I think it has to do with my position as a photographer. I don’t arrive looking for the exceptional or the spectacular. I always position myself in the same spot, at the same time, at the same distance, and I wait. That forces me to accept that everything that happens in front of the camera is part of the same normality.

When you don’t create hierarchies, when you don’t decide beforehand what is important and what isn’t, the most absurd or disconcerting scenes are photographed with the same calm as the most mundane. And perhaps that’s where that feeling of strangeness arises: not because the scene is unreal, but because the camera doesn’t emphasize it or judge it. It simply accepts it.

Q We live in an age of visual saturation and accelerated image consumption. Do you think documentary photography still has its own space and a clear function today?

A I think documentary photography still makes sense, but its function has radically changed. It’s no longer a tool for “showing” what isn’t seen, because today almost everything is visible. The challenge lies in looking differently, in slowing down, in constructing contexts and time.

Faced with the saturation and rapid consumption of images, documentary can offer something very valuable: an experience of duration, of repetition, of attention. Not so much an immediate answer, but a space for doubt and discomfort. In that sense, I continue to deeply believe in the long-term project.

In the end, as Foncuberta once told me, “a lot of anything is interesting.” I’m probably still a collector of trading cards.

Q A question I always ask myself: If you had to name some photographers you admire and who have inspired you, both past and present, who would they be?

A At 54, the photographers who have influenced me tend to be older than me or deceased.

I admire Cristina García Rodero’s work ethic, Joan Fontcuberta’s attitude, Castro Prieto’s technical excellence, Paco Gómez’s (the living one) intelligence, Laia Abril’s tenacity, Cristóbal Hara’s freedom—in short, there are many Spanish photographers

with whom I share this path and who, like me, follow the trail of photography. Photographers like Martin Parr, with whom I’ve shared more than one paella, or Harry Gruyaert, Luc de la Haye, Carl de Keyzer, Larry Sultan, Chris Killip, Richard Billingham, Avedon, Joel Sternfeld…

In short, my Spotify playlist is very long. But I must say that, on a personal level, I have been more influenced by literature and popular science than by photography itself. Authors such as Yuval Noah Harari, Ursula K. Le Guin, Daniel Dennett, Robert Sapolsky, Richard Dawkins, Oliver Sacks, Isaac Asimov, Carl Sagan, and John Steinbeck have provided me with fundamental tools for building the intellectual framework upon which my images rest.

Ultimately, each of my projects forms part of the same imaginary world, which unfolds over time and always draws from the same sources.

And perhaps that is the most fascinating thing about culture: that each link generates new currents that feed a common river, a constantly moving space in which we are all invited to participate.

If you like this content please support the author + Woofermagazine and share it :

HOTEL STORIES

Alfredo Oliva Delgado shares with us the emotions he has experienced in some of the hotel rooms he has visited

UTOPIA

Photographer Attilio Bixio tells us about the failed attempt in the middle of the last century to repopulate rural Italy.

WHEN YOU LIVE IN A SMALL PLACE

Marco Guidi investigates whether growing up in a demographically small place can be a limitation to one’s ambitions.

RODINA

With the book Rodina, photographer Dimitris Makrygiannakis establishes a visual dialogue with mortality.

EYES ON WILSON

An inland North Carolina town documented by 67 international photographers.